Civil War Notables Who Attended Cheshire Academy

The following men attended Cheshire’s Episcopal Academy (now Cheshire Academy) and later served in the Civil War in various capacities: Gideon Welles served as Secretary of the Navy in the administrations of Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson; Georgia native Joseph Wheeler attended West Point after leaving the Academy and when the Civil War broke out he joined the Confederacy; and Andrew Hull Foote – who grew up in Cheshire – joined the U.S. Navy and rose through the ranks to become a Rear Admiral. Bios of these interesting men will soon be forthcoming on Cheshirepedia!

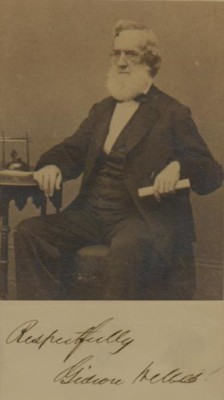

Gideon Welles by John Fournier

Photo courtesy of the author.

“It is vain to expect a well-balanced government without a well-balanced society.”

Gideon Welles, 1835

Gideon Welles, native of Glastonbury, Connecticut, was born on July 1, 1802. Among the many positions he held after his student years at the Episcopal (Cheshire) Academy included being an editor of The Hartford Times, member of the Connecticut General Assembly, Postmaster of Hartford and eventually Secretary of the Navy in the administrations of Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson. And The Diary of Gideon Welles has long been a mainstay in Civil War and Reconstruction research since its first publication in 1911.

Abraham Lincoln nicknamed him “Father Neptune” while critics such as General George McClelland called him a “garrulous old woman.” His strict morality and honesty often set him at odds with fellow politicians and cabinet members, especially when dealing with political appointments and naval contracts while serving as Secretary of the Navy.

How did a young lad of 17, who set out from his home in Glastonbury with his younger brother Thaddeus to ride by horseback to Cheshire to attend the Episcopal Academy, eventually become one of the most important figures in Connecticut history and national politics?

Gideon Welles’ father, Samuel, decided by the time Gideon was 17 that his teenage son needed to prepare “for the duties of life.” After consulting with fellow legislator Samuel A. Foot – whose sons Andrew and John were attending the Cheshire Episcopal Academy – Welles’ father persuaded Gideon to enroll in the Academy. On an early Tuesday morning in September 1819 Gideon Welles and his brother set out for Cheshire.

Cheshire in 1819 had a population of just over 2,200 people and was primarily an agricultural town. The Academy in the early 19th century was still a small school growing in reputation. Bowden Hall was the one learning facility and the school possessed a small library of less than 200 volumes. Welles did not immediately find the two years he spent in Cheshire as particularly rewarding, with the exception of a few associations and friendships that developed. One of these associations was the aforementioned Andrew Foote. Foote left Cheshire soon after graduating the Academy to enlist in the Navy in 1822 and in his lengthy career eventually became a Rear Admiral to serve with great distinction during the Civil War. Welles later admitted that his time at the Academy did change him, “an improvement which I shall never again expect in twice that period.”

The Civil War was still 40 years off when Welles left the Academy in 1821. His initial pursuits into the law proved unsuccessful but by the age of 24 he decided to engage in a career in journalism. Welles joined the staff of the Hartford Times newspaper. Then under the editorial direction of owner John M. Niles, the Times became an advocate of Jeffersonian-Democratic political views. [Newspapers in the late 18th and 19th century were often organs of political parties and machines.] Soon Welles became embroiled in Democratic politics and his interest in politics intensified. He was elected to the state legislature in 1827 and served until 1835, all the while working at the Times. As Niles himself became more involved in Democratic politics, eventually becoming a U.S. Senator and Postmaster General in Martin Van Buren’s administration, Welles took over more editorial responsibilities at the Times. Welles’ views during this period showed a decidedly Jacksonian viewpoint: an emphasis on popular democracy, suffrage for all men [meaning white men – women did not have the right to vote until 1919], Manifest Destiny and suspicion of any federal encroachment on states’ powers and rights.

His tenure at the Times and his involvement in state and national politics throughout the 1820s and 1830s brought Welles to the attention of three successive Democratic administrations: Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren and James K. Polk. Welles enjoyed the fruits of party loyalty by being appointed by President Jackson as Postmaster of Hartford (1836-1841) and by President Polk as Chief of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing for the U.S. Navy (1846-1849).

His involvement in naval matters during the late 1840s, though not exactly political in nature, would assist him enormously later during his tenure as Secretary of the Navy. His previous experience in business, politics and administrative positions provided a solid foundation for his first federal appointment and throughout this period in Washington he began to broaden his outlook on the national scene. For during his appointment in the Navy Department the Mexican War brought unintended consequences to the country and to Welles’ political career.

The enormous land acquired by the United States after the Mexican War ended brought the question of slavery to the forefront of the national political scene. The Compromise of 1850 and, especially, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, threw off the balance of free and slave states that had been the previous status quo and realigned political parties from economic and ideological alliances to sectional loyalties.

Gideon Welles had never been a strong advocate of abolition. But his Connecticut upbringing had also reinforced a feeling of revulsion at the notion of the institution of slavery. Subsequent to the end of the Mexican War southern Democratic politicians attempted to expand slavery beyond its traditional boundaries of the Deep South. Welles increasingly found himself alienated from the Democrats and finally in 1854 declared himself with the newly formed Republican Party. He helped establish the state Republican paper, the Hartford Evening Press, in 1855. Welles then ran for Governor on the Republican ticket in 1856 but lost the election.

Welles continued to run the Hartford Evening Press throughout the rest of the 1850s, espousing Republican Party ideas: primarily free labor and opposition to the expansion of slavery from where it existed. Disunion and states’ rights became more frequently spoken about throughout the nation as the 1860 presidential campaign approached and whoever was going to be the Republican nominee that year would more than likely be elected President.

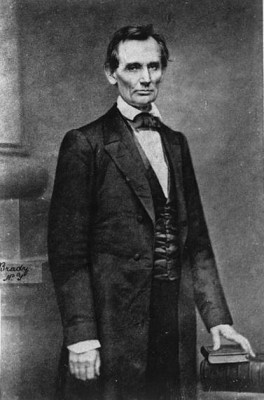

On March 5, 1860 a tall, lanky, 51-year-old lawyer walked from his hotel in downtown Hartford to the corner of Main and Asylum Streets and stopped at Brown and Gross’s bookstore to meet with Gideon Welles. The lawyer was on a speaking tour of the Northeast and on the previous evening in Hartford he reiterated much of what he said at a speech at New York’s Cooper Union a week earlier: slavery’s expansion into the territories was contrary to what the Founding Fathers intended. The lawyer would soon, in turn, have an enormous impact upon the life of Gideon Welles. The lawyer’s name was Abraham Lincoln.

Abraham Lincoln, photograph taken by Matthew Brady on February 27, 1860.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Next: “Father Neptune” Leads the Navy During the Civil War.

John Fournier is a contributing writer to Cheshirepedia.

Coleman, Marian Moore. The Cheshire Academy. The First Twelve Decades. Cheshire, CT. Cherry Hill Books, 1976.

Gienapp, William E. and Gienapp, Erica L., eds. The Civil War Diary of Gideon Welles. Urbana and Chicago. The University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Niven, John. Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy. New York. Oxford University Press, 1973.

http://www.cheshireacademy.org/ftpimages/246/misc/misc_32359.pdf

Andrew Hull Foote by John Fournier

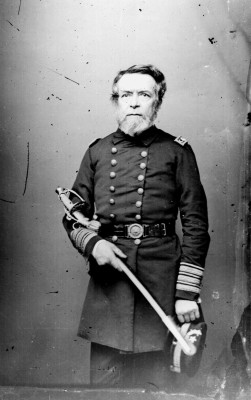

Rear Admiral Andrew Hull Foote, United States Navy

“He prays like a saint and fights like the devil.”

A man who was called “the Stonewall Jackson of the American Navy” had deep roots in Cheshire and Connecticut. Andrew Hull Foote’s ancestor, Nathaniel Foot, was among the first English settlers in Connecticut. John Foot, Andrew’s grandfather, was pastor of the Cheshire First Congregational Church for almost half a century and built the Foote House, which is still standing on the corner of Cornwall Avenue and South Main Street. His father, Samuel A. Foot, was Governor of Connecticut as well as a U.S. Congressman and Senator.

Andrew Foote was born in New Haven on September 12, 1806. In 1813 he and his family moved to Cheshire and resided in the house his grandfather built. [Andrew Foote added the “e” to the end of his name early in life.]

Called a “lively, robust boy” Foote spent his youth in Cheshire and in 1815 his father had him attend the Episcopal Academy. Classmates found Foote to be adventurous and amiable and after six years Foote graduated from the Academy.

At some point in his early life Foote decided that the sea would be the intended vocation for him. After graduating from the Episcopal Academy in 1821 his parents prevailed upon him to attend the Military Academy of West Point instead of pursuing a life in the Navy. He only lasted but six months at West Point and in 1822 accepted an appointment in the Navy where he was appointed acting midshipman. During a cruise in the Caribbean in 1827 Foote experienced a religious conversion and from thence forward he determined to lead a Christian life and increasingly became temperate in his actions and an advocate of temperance reform in the Navy.

Foote continued to be promoted in the Navy, serving his country from the south Pacific to the Mediterranean and circumnavigating the globe in the sloop USS John Adams in 1837. In the 1850s he patrolled off the African coast looking for slave ships and became a firm supporter of abolitionism.

By the time the Civil War broke out in 1861 he was Commandant of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He commanded the Union flotilla in the West in April, 1862 and, along with General Ulysses S. Grant, was instrumental in the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson, thus helping to secure the upper Mississippi River Valley for Union forces. Slightly wounded in the leg during this campaign he was nonetheless raised to Rear Admiral on July 16, 1862. His leg wound refused to heal, however, and he was reassigned to desk duty in Washington. By June, 1863 he was well enough to resume active duty and was appointed Commander of the South Atlantic Blocking Squadron. However, Foote was struck with Bright’s disease in New York and he died on June 26, 1863.

He married his first wife, Caroline Flogg of Cheshire, in 1828. They had two daughters but one of the daughters died at four and Caroline herself died in 1838. He remarried in 1842 to Caroline Augusta of New Haven and she bore him five children.

Foote is buried in Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven.

Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy from 1861-69, was an older classmate of Foote’s at the Academy and later in life declared that Foote “was proud of his profession, and did much, by his example and precept, to elevate the tone and character of the Navy.”

Hoppin, James Mason. Life of Andrew Hull Foote. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1874.

Keller, Allan. Andrew Hull Foote – Gunboat Commander 1806-1863. Hartford: Connecticut Civil War Centennial Commission, 1965.

Admiral Foote’s Boyhood Pranks. New York Times, July 24, 1887.

Tucker, Spencer C. American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, LLC. 2013.

Welles, Gideon. The Diary of Gideon Welles. New York: W.W. Norton, 1960.

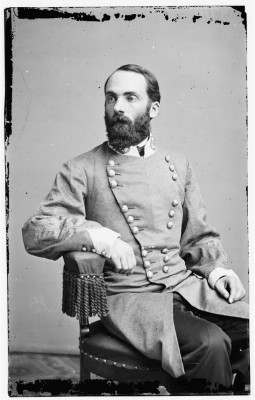

Lieutenant General Joseph Wheeler, Confederate States Army

The Long March Home by Jeanné R. Chesanow

Civil War soldiers on both sides covered hundreds of miles on foot. They often marched all day and into the night – sometimes all through the night to make camp at dawn. The 20th Regiment had forded rivers with water up to their neck; they had slogged through the mucky swamps of South Carolina and the burning forests of North Carolina. The long journey home to Connecticut would be the last trek of the war for these men. They took up their line of march towards Washington DC, homeward bound, on March 30th, 1865, a 274-mile journey northward from Goldsboro NC.

The regiment was in camp at Goldsboro having come there from a series of brutal engagements further south: Savannah GA, Averasboro NC, Silver Run NC, and Bentonville NC. They had come to Goldsboro to “rest, recruit, and be reclothed;”4 the men were issued shoes as well, in preparation for another campaign. On April 10th the regiment set out for Smithfield where units of the rebel army were encamped; the men marched all day through mud and rain, and finally made camp at 10 PM not yet at Smithfield. The next day, April 11, they reached Smithfield after a march of 19 miles. The enemy had fallen back towards Raleigh. On the morning of the 12th, as the soldiers were crossing the Neuse River, they received the good news that Richmond VA, the capital of the Confederacy, had been captured by the Union, and that on April 9th General Robert E. Lee had surrendered the entire army under his command to Lt. General Ulysses Grant! “….what a thrill of joy and gladness runs through this whole army at the mere mention of home!” 4

On April 13th when the 20th entered Raleigh, they saw remnants of the rebel army fleeing and the road strewn with discarded items – food, guns, haversacks. They made camp at Raleigh from the 13th to the 26th of April. On the 24th General Grant arrived with the news that Gen. Joseph Johnston’s rebel army had not given up. There was a truce in place and negotiations were ongoing, but there was a chance that the negotiations might fail and there would be more fighting. Accordingly, on April 28th the regiment moved out to guard the supply train of their division. They marched west towards Jones Cross Roads, about 13 miles, and went into camp with their division. There they got word that the negotiations had ended well; the entire rebel army had surrendered!

So on the morning of the 28th the regiment returned to Raleigh and on Sunday April 30th they headed for Richmond. Their route took them across the Neuse River and the Tar River; they passed near the towns of Oxford, Williamsboro (originally called Lick), and Ridgeway. On the evening of May 3 (two years after the disastrous battle at Chancellorsville VA) they crossed the Roanoke River on pontoon bridges, and were once again in Virginia where they made camp for the night, just north of the river. The next day they were again on the march – across the Chickahominy River and Stony Creek — then by way of Ashland they crossed the North and South Anna Rivers, through Spotsylvania, and reached the tragic battlefield at Chancellorsville. Two years before, in a wooded ravine, a Cheshire soldier William Burke of the 27th regiment, had taken a fatal gunshot wound to his head. And here three Cheshire men from Company A of the 20th had fallen: Corporal Titus Moss, Privates Reuben Benham and John L. Preston; six had been wounded, eight captured. (In the regiment as a whole, 26 were killed, 41 wounded, and 73 captured.) After three days of fighting with huge casualties on both sides, the North elected to retreat, a decision they later regretted.

Now, they are again on that field of battle, Chancellorsville, “where they paused to bury the bones of their brothers that lay bleaching there.” 4 Here, in this now-quiet place, the regiment stopped and camped for the night. Only 60 miles remained in their march towards home.

Jeanné R. Chesanow is a contributing writer to Cheshirepedia.

References

- Buckingham, Philo B. Late Lieut. Colonel Commanding 20th C.V. I. and Brevet Col. U. S. Volunteers, Report to Brigadier General H. J. Morse, Adjutant-General of Connecticut, A report on the movements of the 20thRegiment Conn. Vol. Infantry, from the date of last report to the time it was mustered out of the military service of the United States at New Haven, Conn.” (dated “June 28th, 1865). In: Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Connecticut for the year ending March 31, 1866. pp. 179-181. Printed by order of the legislature. Hartford: A. N. Clark & Co., State Printers 1866.

- Hines, Blaikie. Volunteer Sons of Connecticut. American Patriot Press, 2002.

- Sloat, General Frank D. History of the 27th Regiment C.V.I. In: Ancestry.com. Record of service of Connecticut men in the army and navy of the United States during the War of the Rebellion [database on-line]. Provo, UT:

- Storrs, John Whiting. The Twentieth Connecticut: a regimental history. Ansonia, CT The Press of the Naugatuck Valley Sentinel. 1886. Online edition produced by the Emory University Library Publications Program.

Recent Comments